MPs denounce lack of humanitarian assistance in Myanmar ahead of International Parliamentary Inquiry’s fourth hearing

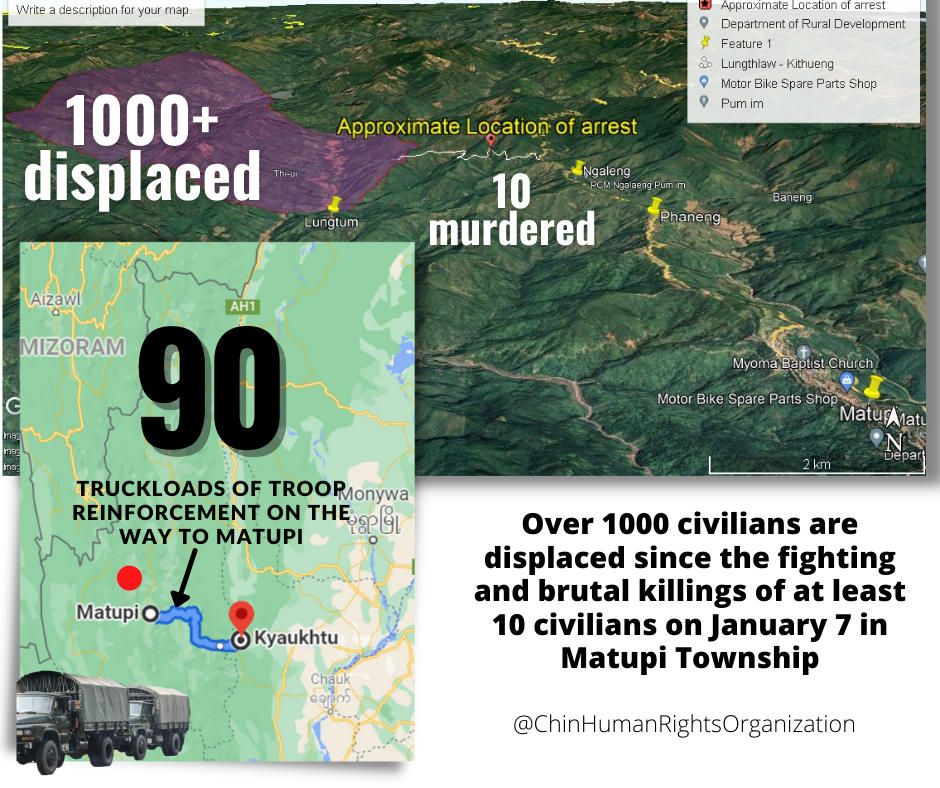

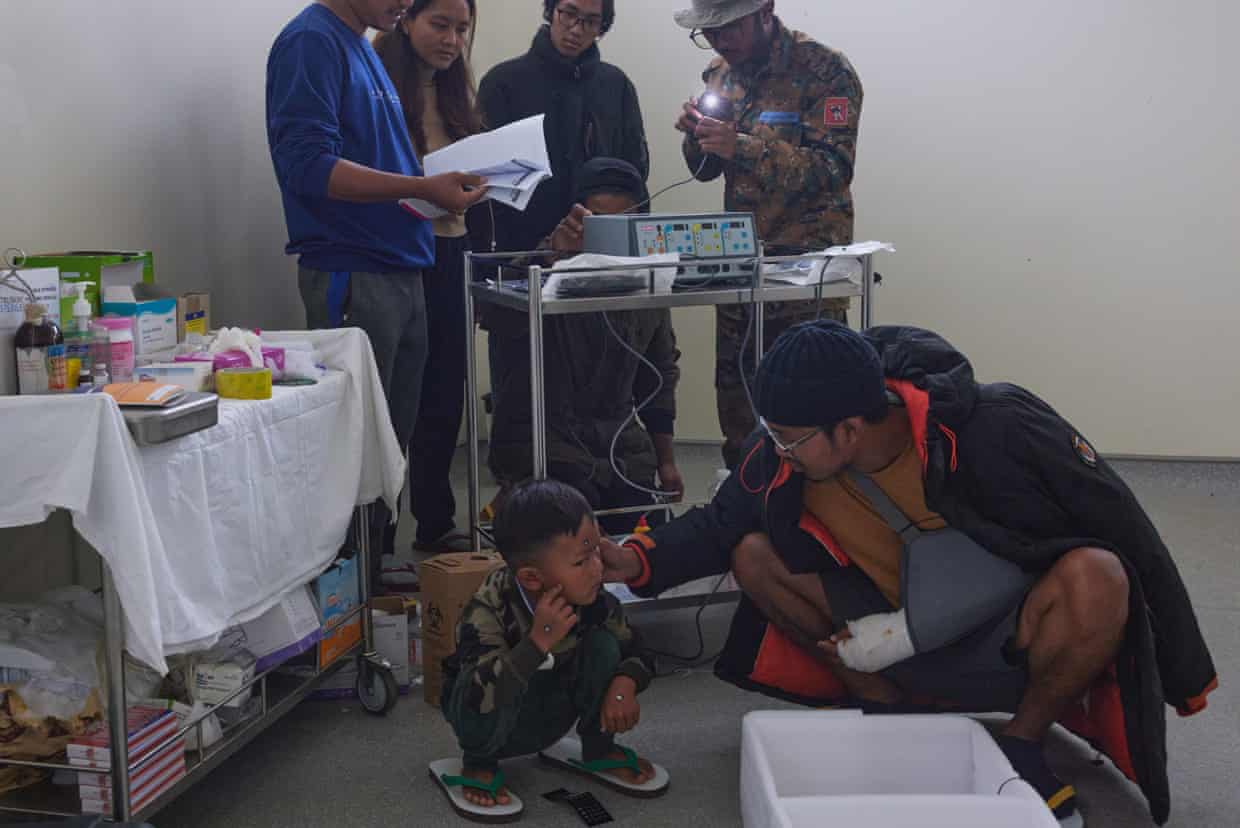

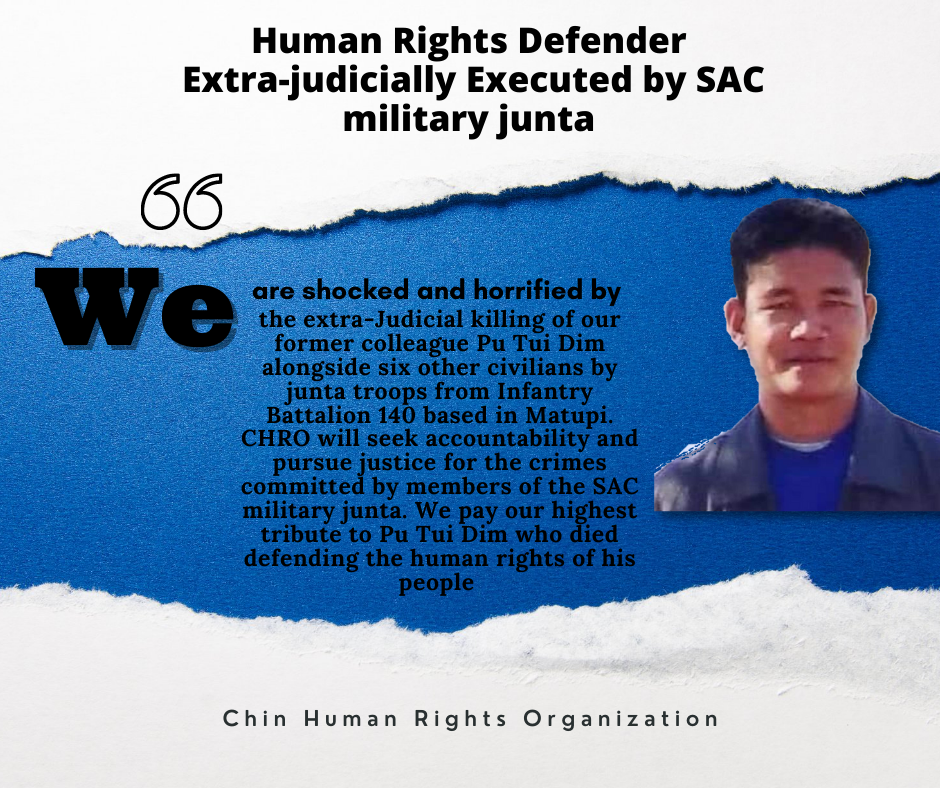

MPs denounce lack of humanitarian assistance in Myanmar ahead of International Parliamentary Inquiry’s fourth hearing – ASEAN Parliamentarians for Human Rights (aseanmp.org) JAKARTA – The Myanmar people are not receiving the humanitarian assistance they need as the crisis triggered by the coup d’état of February last year worsens, parliamentarians from seven different countries in Africa,