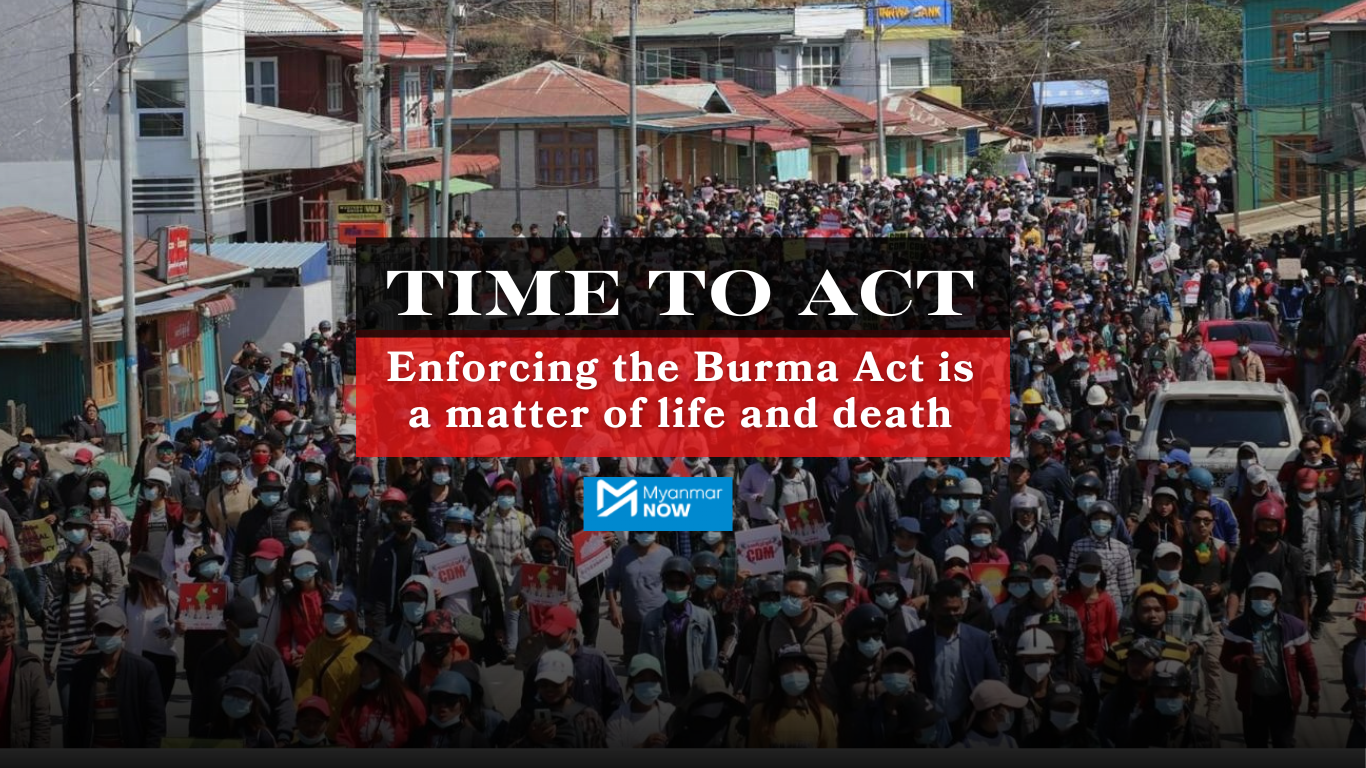

A Christian Call to Justice in Myanmar

Christian communities must not be content with being only good Samaritans. We are called to do more. The teachings of Christ compel us to stand with the oppressed, to challenge the unjust, and to walk with the wounded — not only to tend to them, but to help them rise. Our mission is not only to save lives, but...