Four Years On: Impact of the Coup on Human Rights and Humanitarian Conditions in Western Myanmar

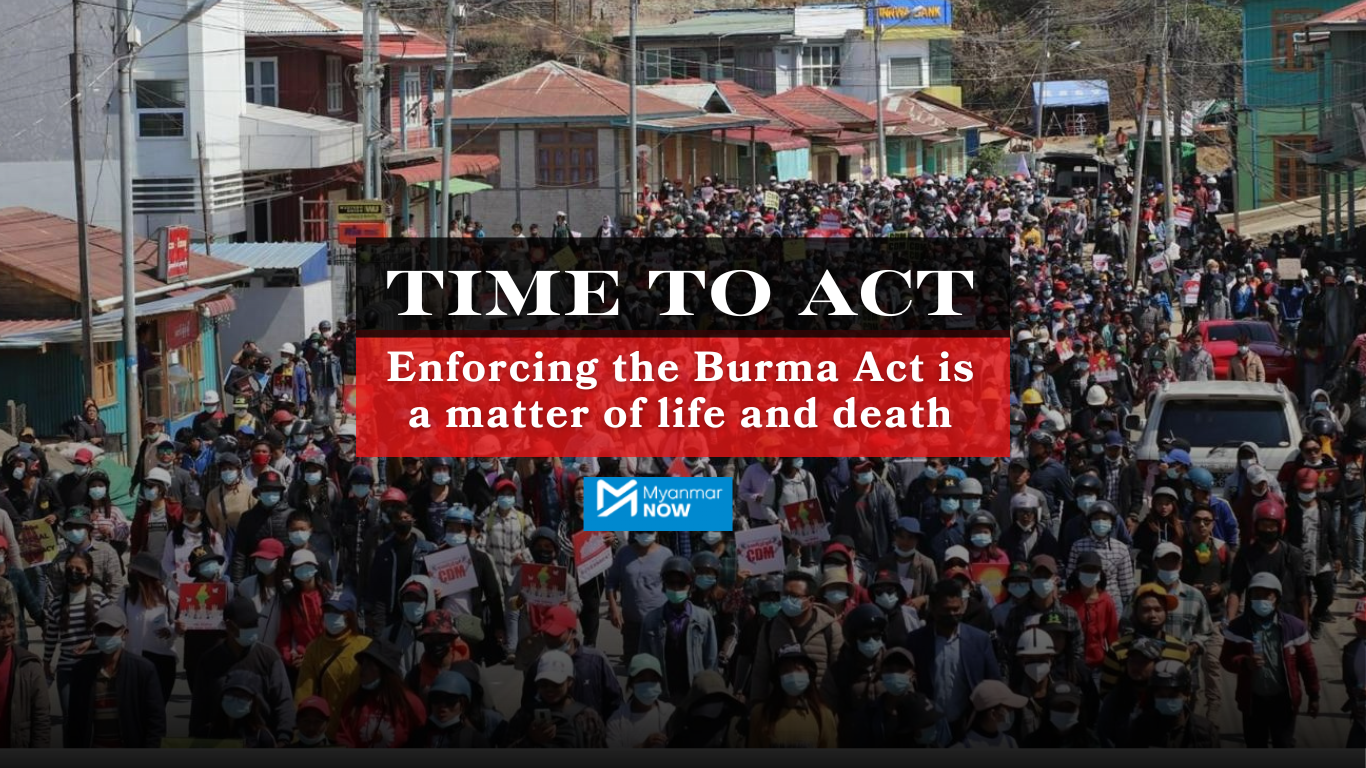

The ongoing humanitarian and human rights crisis in western Myanmar represents one of the most acute yet neglected challenges in the region. Despite its severity, Chin State has often been historically overlooked and underreported, even as it has borne the brunt of violence since the military coup in 2021. Over half of the state’s population