CHAMPHAI, India, Dec 10 (Reuters) – The former boxer said he and his comrades were perched on a hillside near the town of Mindat, in Myanmar’s northwest, and preparing to ambush a patrol of soldiers when the troops opened fire and a bullet smashed into his forearm.

“I tried to run but I got shot again in the upper arm,” Za Latt Thwey, who requested that he be identified by the name he uses as a boxer, told Reuters near a safe house in India’s Mizoram state, which borders Myanmar.

An Indian orthopaedic surgeon’s note said the 25-year-old had suffered a gunshot wound and an X-ray showed where his bone had been shattered.

That skirmish in mid-May was part of what seven people involved in the rebellion, including five fighters, said was a growing popular resistance to Myanmar’s military in Chin state.

Their accounts include previously unreported details of how the rebellion there began and expanded.

As in other parts of the country, civilians enraged by the military coup in February and subsequent crackdown on protesters are taking up arms. The junta appears to be worried about the threat they pose in Chin.

In the last few weeks, the military, known as the Tatmadaw, has sent reinforcements to Chin, which had been largely peaceful for years, and launched a major offensive against rebels, according to some analysts and rights groups.

More than a dozen so-called Chinland Defence Force (CDF) opposition groups have sprung up in the state, according to three of the sources, who described an expanding network of fighters whose knowledge of local terrain is a major advantage.

They said the groups had established supply chains, food stockpiles and weapon depots and linked up with a long-established ethnic group called the Chin National Front (CNF) to train in combat and better coordinate operations.

The military has said all resistance forces and the shadow government are “terrorists”.

CNF spokesman Salai Htet Ni told Reuters the group had helped train Chin youth and protesters in basic guerrilla warfare after the military coup.

“Our unity and public support is our strength,” said a 32-year-old fighter from Chin’s capital Hakha.

Reuters was not able to independently verify some claims made by the sources about the strength of the rebellion and scale of the Tatmadaw’s response.

Myanmar’s military spokesperson and the Ministry of Information did not respond to requests for comment on the growing resistance in Chin or the armed forces’ deployments.

The Tatmadaw’s response to resistance in Chin and elsewhere has prompted warnings from the United Nations and United States that the brutal clampdown on Rohingya Muslims in neighbouring Rakhine state in 2017 risked being repeated.

More than 730,000 Rohingya Muslims fled Rakhine that year and refugees accused the military of mass killings and rape. UN investigators said the military had carried out the atrocities with “genocidal intent”.

Myanmar authorities said they were battling an insurgency and deny carrying out systematic atrocities.

The military has not released details of overall battlefield losses since the February coup.

NOODLES AND SHOTGUNS

Before he took up arms, the fighter from Hakha said he was a postgraduate student of history who joined widespread public demonstrations against the February coup.

Like the four other fighters Reuters interviewed in Mizoram, he said his decision to join the resistance was triggered by the military’s suppression of peaceful protests that demanded civilian rule be restored.

Local monitoring group the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (AAPP) says junta forces have killed more than 1,300 people and detained thousands in a bid to crush opposition to the coup.

The military has outlawed AAPP, saying it is biased and uses exaggerated data. The AAPP has not responded to that accusation.

Groups of young protesters in Hakha began stockpiling food including rice, oil and noodles and medical supplies in multiple locations in the jungle surrounding the township of around 50,000 people, two of the fighters said.

In April, some CDF groups met in Camp Victoria, the CNF’s headquarters, to coordinate armed resistance against the Tatmadaw, according to the fighter from Hakha.

The CNF, which has a military wing, has become pivotal to the resistance, providing training and other support to several CDF groups across the state, said two fighters and a senior leader of the National Unity Government (NUG).

The NUG, effectively a shadow government, comprises pro-democracy groups and remnants of the ousted civilian administration. It has held talks with foreign officials, including from the United States.

In the early months of the resistance, nearly 2,000 volunteers from Hakha were sent to Camp Victoria for combat training under the CNF, the two fighters said, a level of coordination not previously reported.

NEW KIND OF CRISIS

By May, three of the CDF fighters said they were taking on the Tatmadaw in several parts of Chin, a 36,000 square kilometre province with nine major townships.

Outside Mindat, Za Latt Thwey said he was among the guerrillas, some trained by the CNF, who targeted Tatmadaw patrols.

In cellphone footage taken by fighters, and shown to Reuters by Za Latt Thwey, small groups of young men could be seen perched on wooded hillsides firing homemade guns and automatic rifles. Reuters could not independently verify the footage.

Financial support for the rebels in Mindat has mostly come from the Chin diaspora and the NUG, said an ousted Chin lawmaker, who declined to be named.

Through multiple routes, including from India, the lawmaker said food, clothes, medicine and equipment were reaching the rebels each month.

Weapons and explosives were the hardest to procure, according to the lawmaker, the NUG leader and three of the fighters.

The CDF Hakha, with some 2,000 volunteers, is run by a 21-member council that oversees command stations, smaller camps and supporting units, two of the rebels said.

Across Chin violence has escalated in the last four months as the Tatmadaw clashes with a rising number of rebel groups, according to analysis from the Chin Human Rights Organisation (CHRO).

“We have never had this kind of crisis before in Chin,” said CHRO’s Salai Za Uk Ling.

Once a thriving settlement of some 10,000 people, the hilltop town of Thantlang is now virtually deserted, surrounded by soldiers who set alight more than 500 buildings since early September, according to two former residents and the CHRO.

The U.S. State Department singled out events in Chin, and Thantlang in particular, in a statement last month urging the military to end the violence.

Pa Hein, 55, who said he was among the last people to leave the town in late September, told Reuters by telephone that he saw Tatmadaw troops ransack shops and set buildings on fire.

The Myanmar military has denied the accusations, and blamed insurgents for instigating fighting in Thantlang and burning homes.

SEEKING TREATMENT

After the first police defectors trickled into India’s Mizoram state in early March, followed by Myanmar lawmakers and thousands of others seeking shelter, the mountainous border province has become a buffer zone for Chin guerrillas.

The Indian government did not respond to a request for comment.

Mizoram authorities estimate around 12,900 people have crossed over from Myanmar, including 30 ousted state and federal lawmakers, according to a senior Mizoram police official who declined to be named.

Some of the lawmakers and leaders have been helping the resistance, and as fighting intensifies they are seeking to unify and support the rebels.

The NUG wants to bring all armed resistance groups under a single command with the assistance of the CNF, said the Chin lawmaker and senior NUG leader.

CNF’s Salai Htet Ni said the group and the NUG had agreed to work together, with the CNF “taking a leadership role in Chin State’s defence and military warfare.”

After he was shot, Za Latt Thwey said he tried for months to find a safe route to the Myanmar city of Mandalay, but eventually deemed the journey too risky.

In early November, he collected money from family and friends and undertook a five-day journey, mostly by motorcycle, to cross into India.

“I can’t box anymore,” Za Latt Thwey said. “But I need my arm to be fixed so that I can continue my normal life, so that I can farm.”

By Devjyot Ghoshal and Chanchinmawia

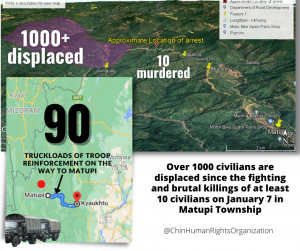

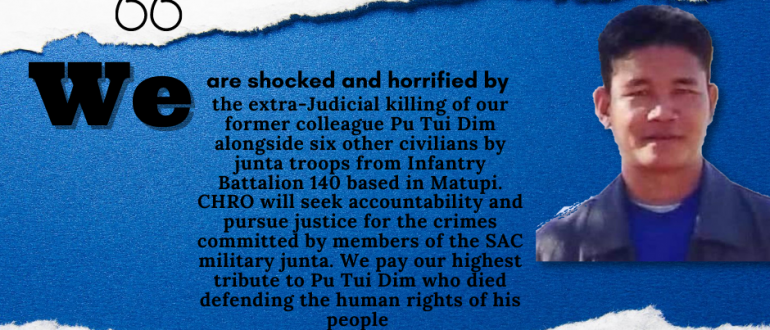

On January 6 at around 8:30 am, junta soldiers from LIB 140 of Matupi-based Tactical Operations Command arrested seven people who were traveling by motorbikes on the road between Kihlueng and Lunghlaw villages, northwest of Maputi Town. The arrests took place at a location about one mile outside of Kihlueng village. One of the travelers in the group is a 56 year-old villager (Name withheld) who turned away and escaped immediately upon witnessing the arrests of his traveling companions who were driving ahead of him. On the next day at around noon on January 7, villagers discovered 8 dead bodies, including that of a 13-year-old boy whose throat was slashed along the stretch of dirt road between Kihlueng and Lunghlaw. All the dead bodies have their hands tied behind their backs and bore knife wounds to the torso area and slashed throats. Two more bodies were discovered at a location between Kihlueng and Kace, another village in the area north of Kihlueng, the same day.

On January 6 at around 8:30 am, junta soldiers from LIB 140 of Matupi-based Tactical Operations Command arrested seven people who were traveling by motorbikes on the road between Kihlueng and Lunghlaw villages, northwest of Maputi Town. The arrests took place at a location about one mile outside of Kihlueng village. One of the travelers in the group is a 56 year-old villager (Name withheld) who turned away and escaped immediately upon witnessing the arrests of his traveling companions who were driving ahead of him. On the next day at around noon on January 7, villagers discovered 8 dead bodies, including that of a 13-year-old boy whose throat was slashed along the stretch of dirt road between Kihlueng and Lunghlaw. All the dead bodies have their hands tied behind their backs and bore knife wounds to the torso area and slashed throats. Two more bodies were discovered at a location between Kihlueng and Kace, another village in the area north of Kihlueng, the same day. 1. Pu Tui Dim, 55

1. Pu Tui Dim, 55 Horrified by news of the brutal killings, more than 1000 civilians from at least six villages in the area, including Kihlueng, Kace, Boitia, Ngaleng, Lunghlaw and Tibaw villages have all fled and are taking shelter at Amlai, Rengkhen and Tangku villages. But as troops are reinforced in the areas, the IDPs, along with civilians from their host villages have further moved towards Sumsen and Sabawngpi, which are located closer to the Indian border. Some have crossed into Mizoram, including a witness to the arrests on January 6 of a group of travelers whose bodies were later found.

Horrified by news of the brutal killings, more than 1000 civilians from at least six villages in the area, including Kihlueng, Kace, Boitia, Ngaleng, Lunghlaw and Tibaw villages have all fled and are taking shelter at Amlai, Rengkhen and Tangku villages. But as troops are reinforced in the areas, the IDPs, along with civilians from their host villages have further moved towards Sumsen and Sabawngpi, which are located closer to the Indian border. Some have crossed into Mizoram, including a witness to the arrests on January 6 of a group of travelers whose bodies were later found.